by Erica Miner

‘San Francisco, a city that considers its Opera only slightly less sacred than the Holy Grail’

San Francisco. City by the Bay. Famous for stunning landmarks: the Golden Gate Bridge, Alcatraz, Pier 39, Fisherman’s Wharf. Legendary for its cable cars, iconic waterfront, steep rolling hills and Victorian architecture. A city of contrasts, from its natural beauty to its technology. Of fascinating history, from the gold rush to the present.

But the San Francisco of Overture to Murder, the latest novel in my Julia Kogan Opera Mystery series, is a city of mystery: Twin Peaks, stealthy fog…and the ghostly upper reaches of its opera house.

After her

life-threatening entanglements in murder investigations at the Metropolitan

Opera (Aria for Murder) and Santa Fe Opera (Prelude to Murder),

intrepid young violinist Julia Kogan takes on new challenges as the

concertmaster (first of the first violinists) of the San Francisco Opera, a

position of immense responsibility. She is temporarily replacing the current

concertmaster, who has been badly injured in a hit-and-run accident, which

Julia thinks worthy of looking into as not accidental. It is a high-pressure

situation for her, both musically and emotionally, but she’s up to the test—or

is she?

In the

historical War Memorial Opera House, Julia finds a theatre steeped in history:

among other things, it’s adjacent to the Veterans Building where Harry Truman

signed the UN Charter in 1945. But she also finds intrigue. There’s no time for

sampling the sourdough, Dim Sum, Ghirardelli chocolates and other culinary

delights of the city. Julia has her work cut out for her, trying to uncover the

perpetrator in the latest grisly operatic killing.

The city of San

Francisco and its opera are in my blood. I have a personal connection with both

of them. Over the last several decades I paid numerous visits to this amazing

city to spend time with a close family member who worked with the company and

with other family members and friends who lived in the Bay Area. Thus I

experienced a doubly significant journey when I recently toured the War

Memorial Opera House with the House Head, who had been working there for over

30 years and knew every corner and cranny. Little had I known that the place,

which had served as the locale for the film Foul Play, is filled with

creaky old equipment that’s positively scary to look at and listen to and is

home to its own ghosts.

As I cringed

from these discoveries, I put myself in Julia’s shoes. How does she cope with

disturbingly creative modes of murder devised by a mentally unhinged killer?

She investigates, of course, as is her wont. Her natural curiosity gets the

better of her, as it has in previous opera houses. She will leave no sheet of

music unturned until she discovers the perpetrator’s identity, with little

regard for her own safety. The trouble is, she’s not the only one who’s in

danger. The life of another person near and dear to her is in jeopardy as well.

The tables have turned.

It was such a trip for me in so many ways to write this novel. Nostalgia about my past experiences with the company met with the fascination I experienced in my forays at the opera house of the present. Julia is my alter ego, based on myself when I, too, was an eager young violinist. But I could never summon up the level of courage that becomes essential for her as she navigates the perilous world of opera mystery in the dark stairways, back hallways, and hundred foot-high catwalks of the War Memorial Opera House. And again, the curtain comes down on murder.

About Erica:

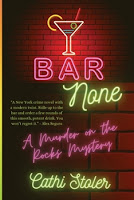

Former Metropolitan Opera violinist Erica Miner is now an award-winning author, screenwriter, arts journalist, and lecturer based in the Pacific Northwest. Her debut novel, Travels with My Lovers, won the Fiction Prize in the Direct from the Author Book Awards. Her current Julia Kogan Opera Mystery series reveal the dark side of the fascinating world of opera: Aria for Murder (Level Best Books, 2022), was a finalist in the 2023 Eric Hoffer and Murder and Mayhem Awards; Prelude to Murder (2023) a Distinguished Favorite in the 2024 NYC Big Book Awards, glowingly reviewed by Kirkus Reviews; and the just-released Overture to Murder (2024). As a writer-lecturer, Erica has given workshops for Sisters in Crime; Los Angeles Creative Writing Conference; EPIC Group Writers; Write on the Sound; Fields End Writer’s Community; Savvy Authors; and numerous libraries on the west coast.

ISBN-10:

978-1-68512-781-7 (pb)

ISBN-13:978-1-68512-782-4

(eb)

Webpage: www.ericaminer.com

Social media:

https://www.facebook.com/erica.miner1

https://twitter.com/EmwrtrErica

https://www.instagram.com/emwriter3/

Buy Link: Amazon

Blurbs:

“Anyone who loves the romance of opera and opera houses will enjoy

Overture to Murder. Miner gives us a unique tour of the War Memorial Opera

House, letting us in on its secrets, legends and gossip, and one of its

most important occupants, the San Francisco Opera. She shares many details only

a true insider can know, bringing the building to life and making it an

essential character in this exceptionally well-crafted mystery.” ~ John

Boatwright, San Francisco Opera House Head

“Divas and deadly secrets share center stage in Erica Miner’s Overture

to Murder, a classic mystery tale set at the San Francisco Opera House,

a chilling backdrop for murder. Precise details, inside information about the

glamorous world of classical music, and a cast of finely drawn characters

propel the action from the opening curtain to the final bows. This suspenseful

tale of mystery, music, and mayhem is a page-turner. Highly recommend.” ~ Lori

Robbins, author of the On Pointe Mysteries

“Set against the elegant backdrop of the San Francisco Opera, this smart, suspenseful mystery weaves a tale as intricate and compelling as Wagner's Ring. With its masterful blend of suspense, music, and drama, OVERTURE TO MURDER is a must-read for mystery enthusiasts and opera lovers alike. Mally Becker, Agatha Award-nominated author of The Revolutionary War mysteries.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)