How often, when you’re reading, do you encounter words or phrases with which you’re not familiar?

It probably happens to all of us occasionally.

But when we’re writing, we have to keep in mind the little detail that we do want our writing to be understood by our readers.

Sometimes I’m surprised at words I use that are part of my working vocabulary but trip up my critique partners. Familiar words can have multiple meanings, and that can throw our readers off, too.

We all have some specialized terms that come from our own experience, and it can be hard to figure out when we need to help our readers to understand what we’re saying without slowing the story down.

The first time I seriously encountered that problem was in a short story about a homeless veteran who had built a shelter under a bridge approach. I mentioned something tumbling down the riprap to the water.

Surely everyone knows what riprap is.

But a couple members of my critique group questioned it.

It’s the rocks or stone placed on a steep bank to control erosion. (Everyone knows what a bank, as used here, is. Right?)

I set myself a rule of thumb. If one person questions a word, I go back and make sure it is commonly understood in the way I intend.

If two or more people question it, I either change the word or add contextual clues.

Sometimes I know I need to provide the clues when I want to use a word. If a character is going to wait by the “voe,” I’ll add, “where a finger of the sea pierces the rugged shore.” I’m less certain that I need to supplement “on the ebb” with the clue that it’s when the tide goes out, but I’ll do it anyhow.

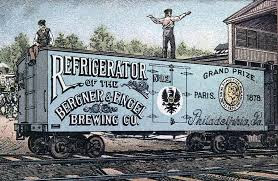

In an industrial/warehouse setting served by railroads, I know that if my protagonist is going to end up locked in a “reefer,” I’d better explain that it’s a refrigerated boxcar with a finite oxygen supply. But how many people will not know what a railroad “siding” is? Some, apparently, especially if it ends in a “spur.”

Also in an industrial setting, when a victim is sent through a “powdercoat booth and oven,” emerging painted orange and very dead at the end of the processing line, I know I’d better do some setup about how powdercoat painting and finishing works before we get to that point.

One of my recurring protagonists is on parole from a murder conviction. He copped an Alford plea. I think most people are familiar with the “cop a plea” terminology, but the Alford plea may need a bit of explanation. It’s when someone denies having committed a crime, but concedes that enough evidence exists to convict.

An example often used is the poor fellow who has a shouting match in public with his girlfriend, including issuing threats to “take care of” her, and storms out. When he seeks her out to apologize, he finds her stabbed to death on the floor of their apartment. In his horror, he picks up the knife used to kill her. At that moment, the police arrive to find him standing over her with the murder weapon in his hand.

His best bet may very well be an Alford plea. One of the drawbacks of such a plea is that, if he denies having killed her, he can’t express remorse to the parole board. And the parole board is looking for remorse.

How about “toggle switch” or “coal breaker” or “homeplace?” To me, they sound like common terms, but some critique partners have questioned them.

I’d hate to leave my readers on “tenter hooks” (those are hooks used to stretch wool or linen fabric on a tenter frame while it dries, and so referring to someone left anxiously hanging. Definitely not “tender hooks”) about what’s happening in the story.

Words with multiple meanings, like the aforementioned “bank,” can cause problems, too. I once had a real go-round with an editor on the word “start.” Of course it can mean “begin.” But it can also be used “with a start” in the context of startle. I try to save my arguments with editors for important issues, so I just changed the phrase.

But it does raise the question: can we have a fleeing character who, upon encountering an unexpected obstacle, “stops with a start?”

Can you remember instances in which you had to pause your reading to figure out what an author meant?

Another whole area are referential works: things as a writer you "expect" your reader to have as part of their knowledge framework. But they are older/younger, more or less educated -- in short, not you. And so that perfect comparison to dem Brooklyn Bums falls short because most of the world grew up long after the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to LA (1958), and besides, who watches baseball anyway?

ReplyDeleteLOL - I remember the Brooklyn Dodgers AND my dad made sure to take me to Ebbets Field to see a game before they left. I was 6 and all I remember is that the hotdogs made the buns soggy.

DeleteI was in a Bronx Bomber family growing up. (I don't remember the hot dogs, but I loved the Cracker Jacks.) And you're right, Jim; I don't watch (or even follow) baseball any more. Although some of my siblings make annual pilgrimages to Florida pre-season.

DeleteYes, yes, yes. The publisher of one of my series is in London, so I've gotten notes during the editorial process regarding phrases that those of us on the US side of the pond have no issues with. But since they're targeting the UK and European markets, I don't even explain or argue. I simply change the wording. I've given up trying to figure out in advance what's going to stump them, but it's an interesting experience trying to learn English English.

ReplyDeleteI have a book titled British English from A to Zed that helps, although I'm sure it's dated now.

DeleteAnnette, that's an entirely new area you're exploring. I remember the horrific reaction when some British executive described drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico as a "scheme." In American English, it would merely have been a plan or a project. No nefarious implications.

DeleteIf I can't figure out a word from context, I'll look it up.

ReplyDeleteI do that too, Margaret. But I don't know that we can expect our readers to stop reading and look things up. They might just stop reading entirely.

DeleteAs a reader, I love the Kindle dictionary feature that provides options! As a writer, Especially one whose writing includes the specifics of diving, I try to double think any terms of art. That also includes boating terms. A recent book referred to the ship being stocked to the gunnels. Yep, that is the pronunciation, but the spelling is gunwale. It bothered me because boats are a large part of this author’s book.

ReplyDeleteThe one editor battle I considered fighting was the use of the term Doubloons in a title. The editor claimed no one would know what Doubloons were. I changed the title, and defined the term the first time it appeared in the book, but I’m still not convinced it would have been an issue.

I know what doubloons are. Interesting how the Spanish-origin terminology for money has entered our language. We call a quarter "two bits," which originally referred to one-fourth of a coin called "pieces of eight." Spanish coins were international money in the way that dollars or euros are today.

DeleteI find it annoying when a much younger editor with a more limited vocabulary questions words I use. I don’t believe in dumbing down my words because they don’t know them. I learned unfamiliar words because I looked up their definition when I came across them.

ReplyDeleteGrace Topping

I think we've all encountered inexperienced editors who have no idea what we (or they) are talking about. It does make me appreciate the professional editors with whom I've been privledged to work.

ReplyDelete